“Malays are lazy”, “look at those black-skinned people”, “it’s always the Indians who are the smelliest”. These are the casual racist remarks that I have grown up listening to. Being brought up by racist Chinese parents has inevitably engrained some of their ‘conservative’ ideas in my own head. However, an open mind, paired with being born in the era of the internet, has allowed me to backpedal and unlearn these prejudices.

Whenever I attempt to start conversations with my family about racism, they are often closed off to the idea and remain adamant that their statements are just ‘facts’. These often turn into emotionally charged conversations that gear towards aggression from a lack of understanding. Hence, I have always wondered: How can we talk about racism?

This was the topic for the Possibility Conversations held in August, a monthly virtual platform held jointly by A Good Space, serve.sg and socialcollab.sg. Mohamed Imran Mohamed Taib, Shamil Zainuddin, and Nazhath Faheema came forward to share their knowledge on how we can tackle these sensitive conversations. Recognising the complexity of this issue, the event was not about providing solutions but rather, for the speakers to come together and share ideas on how they thought we could better discuss race and racism. Here are some of my key takeaways from that session.

Imran kickstarted this month’s Possibility Conversations by explaining how race as a concept is an invention from the 17th Century. Back then, the Europeans started categorising people based on physical traits instead of where they were from, and emotional traits were even attached to these races. Because these segregations were viewed mostly through the lens of ‘science’, they were considered ‘legitimate’ and socially acceptable back in the day.

This racial division was brought to our shores when the British ruled Singapore. It was during this period when racial stereotypes, such as the lazy indigenous Malays and Filipinos, were introduced into our society simply because these communities refused to participate in the capitalist, exploitative system of British rule. This was when the categorisation of races CMIO (Chinese, Malay, Indian, Others) was first brought into Singapore, made to fit the British order.

Do you ever question how often we attach racial stereotypes to people’s undesirable actions? This mindset showcases the need for us to question our assumptions, or “fight our inner demons”, as Imran put it. When someone comes forward to share their experiences of racial discrimination, we should listen with empathy and withhold judgement. More importantly, we should interrogate ourselves internally on why we have the tendency to dismiss another’s experience of racism.

Before we talk about race, Imran challenges that we need to first investigate our own lens on how we view race, as it may hinder the way we see problems in conversations on racism. Hence, Imran questions the audience: are we brave enough to interrogate ourselves and our own views? It may reveal our privilege and blind spots.

When the topic of race and racism is brought up, it is hard to miss the intersections that lie within this discourse. Another key idea that was brought up was that people of different social classes have varying abilities to call out racism in society.

A janitor in a big company does not have the same privilege to call out their bosses for being racist as compared to a client of that same company, for instance. This gap in social class and position makes it challenging for certain groups of people to start conversations on racism.

Imran illustrated it like this; the stereotype of Malays being lazy cannot be addressed by Malays of a lower social-economic class, because they may not have the power to reverse this stereotype. How much certain stereotypes hurt depends on the person at the receiving end and their relative position in society. Higher class Malays, in this example, might not feel the same kind of hurt towards stereotypes as compared to lower class Malays. Moreover, if said person has a lower status in society, it becomes more offensive as it adds to their lived realities.

Hence, discussions on race and racism cannot be held unless we acknowledge and talk about the intersections it has with social class, both within and across communities.

I’m sure many of us have heard of safe spaces. Indeed, many conversations on racism seem to be held in these spaces. However, Imran argues that safe spaces are not sufficient to talk about race and racism. Instead, he emphasizes the distinction between Brave Spaces and Safe Spaces.

Safe spaces provide psychological and emotional security, where people share their personal stories expecting comfort and support. However, the question then becomes whether we are aware of our positions in these stories. When we do not evaluate our own positions, the intricacies of our stories could potentially make others’ stories unsafe.

In contrast, brave spaces encourage mutual learning and accountability. Essentially, brave spaces are all about transformative dialogue; holding each other accountable in their stories in an interconnected and interdependent manner. To be ‘brave’ means stepping out of our comfort zones and accepting the pain and discomfort that comes with a change in thought, feeling and behaviour. It is unlearning what you think you knew.

For instance, in terms of racism in Singapore, a person of privilege has to acknowledge his advantage and lack of barriers in society compared to others, and he must come to terms with that in a brave space. If he does not, his sharing of his personal narrative will only serve to reinforce the current inequalities present in our society.

Furthermore, these brave spaces should provide people with the security to ask sensitive race-related questions. This is to ensure that they do not let such questions that could cultivate cultural stereotypes and negative thoughts fester. Therefore, it is quintessential for conversations on race and racism to be held in brave spaces.

Racism is an ongoing issue, and many often provide advice on actionable steps that we can take. However, Faheema’s stance is that we should not be providing solutions in these conversations from the get-go, but first developing an opinion from a learned point of view. How exactly does one do this? Simple: by learning and reflecting.

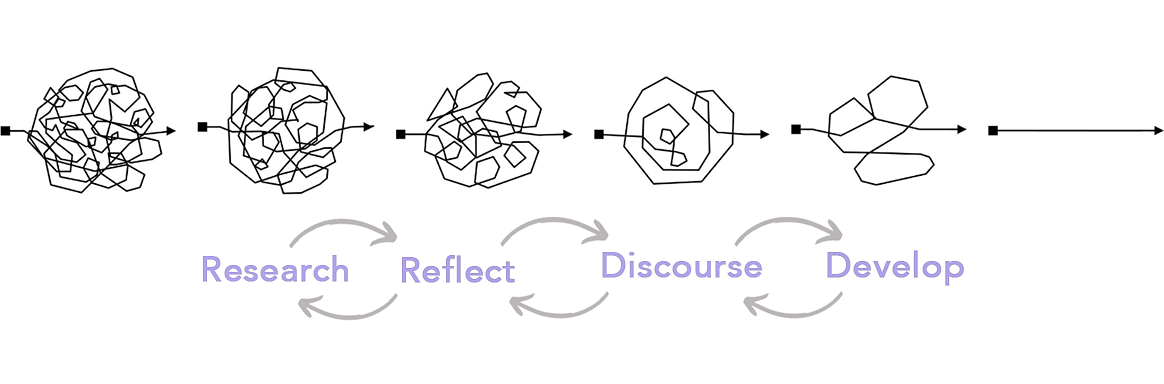

With hash.peace, Faheema has developed the R2D2 framework: Research, Reflect, Discourse and Develop. This framework encourages reviewing information from Research on race and racism before Reflecting on said research to form an informed opinion. Discourse follows next, which is where dialogues on racism are held. Lastly, Develop aims to create well-reasoned conclusions crafted from the above steps and create advocacy projects based on these conclusions.

Essentially, Faheema wishes to promote responsible advocacy with this framework to ensure that we are better equipped to have conversations on race and racism.

Faheema also shares that change can happen just by shifting two to three degrees, that we do not need significant changes in order to talk about racism. During her internships, she would volunteer to do a Racial Harmony Day event at her workplace to encourage more conversations on race and racism. She encouraged people to have more dialogues on religiously motivated extremism and Islamophobia in order to counter them.

Hence, following the R2D2 framework and making small changes along the way can go a long way in opening people up to talk about race.

The conversation then touched on the existence and history of the CMIO framework, which is the governmental categorisation of races, namely Chinese, Malay, Indian and Others respectively. As mentioned by Imran, CMIO is a relic of our colonial past and rules our society from day to day.

This begs the question: Why does it have to be CMIO? Why haven’t we been considering the other combinations? MCIO? MICO?

Shamil’s approach is simply to change our perspectives: Instead of CMIO, what about OMIC? His idea is that we do not need a grand gesture, we just need to start by putting others first. This concept is not restricted to just race, we can expand the ‘Others’ category to migrant workers, low-income families, and a myriad of other marginalised groups in Singapore.

This could easily be achieved through small changes. For instance, governmental organisations can change the sequence of race selection in their forms: from CMIO to OMIC. This could start the fundamental shift in how we define ourselves in relation to others by making it a habit to instinctively put others first. Furthermore, OMIC can also stand for ‘others matter in the community’.

Shamil also wonders if having a form of OIMC that sounds more fun can help to open up more conversations on what it means to put others first, like addressing each other by kinship names like abang, auntie, bro.

The general consensus from the conversations held during the session was that fighting fire with fire usually results in emotionally charged arguments that are not constructive. This case in point can be seen in my own experiences with my parents whenever I try to talk to them about racism. This is also often seen in our youths where the concept of ‘cancel culture’ is prominent on social media.

Imran notes that we need to foster good relationships with the people we are attempting to call out in order for the conversation on racism to be held productively. This idea does not translate to online platforms as these relationships are not built upon and nuances are often not picked up.

How exactly do we cultivate this idea of calling racism out in a constructive way to adolescents? They may be more concerned with how they are perceived as “socially woke” than being respectful of others’ dignity. Is there a way of educating them to recognise that their words could do more than just harm to other people and that they should go beyond conforming to social norms?

Conclusion

At the end of the session, I was in awe at all the insights that the speakers had divulged to us. My main takeaway was on the distinction between safe and brave spaces as well as the need for us to assimilate ourselves into brave spaces when we talk about racism.

My initial impression was that safe spaces were sufficient to talk about sensitive topics. After all, safe spaces were a concept that was familiar to me. However, attending Imran’s breakout room where he further elaborated on the need for us to acknowledge our positions and being open to being uncomfortable with unlearning who we are was eye-opening to me.

This month’s Possibility Conversations on racism has also opened up various possibilities in what we can do to contribute and start conversations on race in Singapore.

If you have made it to this point and are wondering what you can do, consider the following opportunities and questions:

- How might we educate our adolescents in order to open them up to conversations on race and racism early on in their lives?

- How might we implement the concept of OIMC into our everyday lives?

- How might we create brave spaces in workplaces in order to facilitate conversations on race and racism among employees?

Amanda Tay

Amanda is a digital marketing trainee at A Good Space. To her, nothing beats lying down after a fulfilling day with a good anime playing and a warm cup of green tea in hand.