If you live in Singapore, you’ve probably heard of the tragic death of Piang Ngaih Don, at the hands of her employer, Gaiyathiri Murugayan.

More horrifying is the fact that Ms Piang’s case is not an isolated one — as MaidForMore’s #nomoreFDWabuse campaign notes, 18 foreign domestic workers have been abused, murdered or have died by suicide in their employer’s home since 2001.

These are only cases that have received media coverage.

Recently, a commentary by Shamsul Kamar, titled “Pluralistic ignorance and why overcoming it can prevent abuse of domestic workers” was published on Channels News Asia.

Kamar terms “the bystander effect” as “pluralistic ignorance”, noting that these cases of abuse could have been prevented if bystanders had taken action to intervene or report what they have witnessed. He writes, “Bystanders assume that somebody else will help if the situation is indeed life-threatening, and therefore are less likely to offer help themselves.”

Perhaps the bystander effect might have contributed to the otherwise unseen (or ignored) neglect and abuse of FDWs. Maybe the fate of those 18 domestic workers could have been very different if the people around them had taken action.

At the same time, I started thinking: Is the bystander effect the most significant factor in domestic worker abuse? Might there be other factors that contribute to the ill-treatment of our domestic workers?

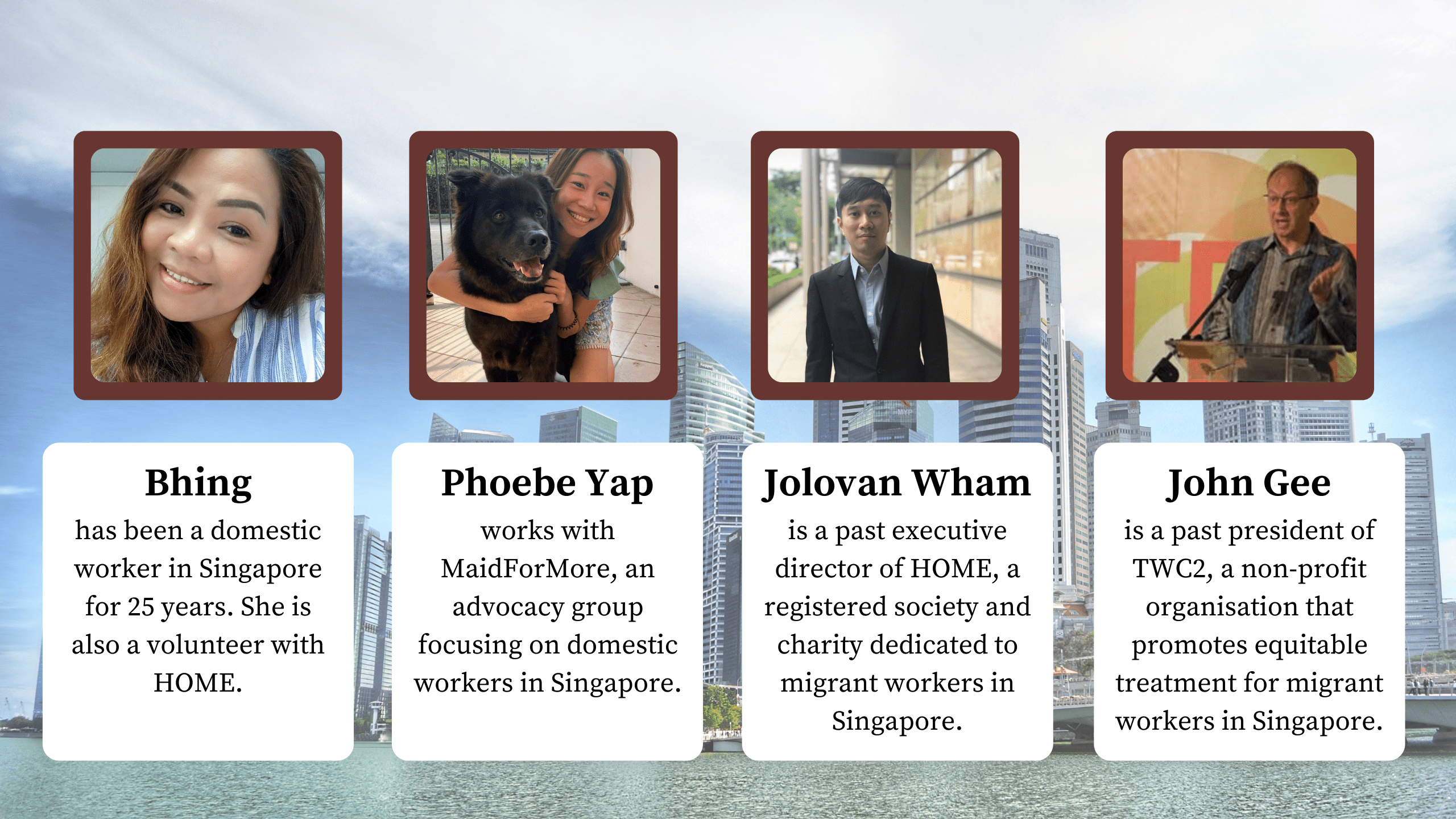

With an admittedly shallow knowledge of the rights of FDWs, I wanted to see if I could learn from changemakers with experience working with FDWs and our domestic worker friends themselves. So I reached out to friends of A Good Space.

Several of the changemakers I spoke with agreed that bystanders could play a significant role in the living and working conditions of domestic workers, especially immediate family members living in the same household or those in the neighbourhood, given how most domestic workers live in their place of work.

Other changemakers brought in fresh perspectives on other factors that might contribute to this issue. Here is what they shared with me.

The bystander effect could stem from the inherent power imbalance between employers and domestic workers

John Gee, a past president of Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) who has been working with domestic workers since 2002, shared that when employers can restrict a domestic worker’s movement from their place of employment, bar them from communicating freely with the outside world or subject them to verbal abuse without consequences amongst other things, the power balance is tipped significantly in the employer’s favour.

In many occasions, the domestic worker is deprived of the power to assert her rights and over time, this unequal relationship is condoned by society as normal. Individuals benefitting from these unequal relationships might not want to make changes that would inconvenience them or they may continue engaging in it because they wrongly assume that the practice is widely accepted.

“Ultimately, giving anyone such power over another individual tends to have a corrupting effect on both the individual who holds that power and on the society that permits it,” he shared.

Over time, this unequal relationship could lead to an entrenched belief that FDWs are implicitly inferior and thus, have to be treated differently, further contributing to the bystander effect.

“Stereotyping of domestic workers to represent them as irresponsible or childlike can be used to excuse confining and controlling behaviour and is often self-serving.” he said.

Phoebe from MaidForMore shared with me that despite laws that mandate giving FDWs sufficient privacy, adequate ventilation, at least 3 full meals a day; or laws that forbid the confiscation of passports and FDWs working outside of their employers’ homes, people could come to an easy justification that FDWs do not deserve these protections and therefore, they do not intervene. She added that this is further worsened by the weak enforcement of such laws.

Bhing, a domestic worker in Singapore for almost 25 years and an active volunteer for the Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME) added that she was not optimistic that instances of reported abuse would be heard, given the reporters of abuse are usually the domestic workers themselves and not locals. “Perhaps the bystander effect can be due to the fear of locals of being labelled as ‘kaypoh’,” she said.

• • •

Social media could normalise a negative perception of FDWs in employers, contributing to more bystanders

Phoebe added that she had come across many Facebook groups where employers convene to share their experiences (usually negative) with FDWs they employed.

“It is genuinely scary to witness how accusations and anger from some employers who had negative experiences can go on to influence a mood of fear in other employers who might not have had similar experiences,” she said.

This has a significant influence on the living and working conditions of FDWs. “Many employers actually decide whether to grant them access to handphones, days off, etc because of these comments and experiences of other employers,” expressed Phoebe.

Her concern was that these Facebook Groups could normalise a negative perception of FDWs in employers, contributing to more bystanders in the cases of ill-treatment. It is the mindset of: “if everyone is doing this, then it should be okay”.

Bhing also shared her experience as a witness to unreported abuse. Her friend, Ms. A, had been overworked and verbally abused during Circuit Breaker and feeling overwhelmed, decided to run away from her residence. Ms. A had only been in Singapore for a month and was new to working as a domestic worker.

As Ms. A sought help from Bhing and HOME, it was discovered that her employer had not given her off-days and lied that it was due to COVID-19 regulations. Both the agent and family members of the employer were aware of this arrangement. The employer had exploited her lack of knowledge and failed to recognise that as a new domestic worker, she needed to be able to socialise and build a support network.

The same employer then made a post on their Facebook account, complaining about Ms. A’s performance as a domestic worker. Alarmingly, when friends of the employer responded to the post, all had sympathised with the employer and rained criticism upon Ms. A. No one had thought to question the credibility of the employer’s account.

“Domestic workers are humans, they are not robots,” said Bhing.

• • •

A lack of trust and paternalistic mindset by employers towards FDWs could contribute to their ill-treatment

In addition to the bystander effect, some of the changemakers I spoke to also offered that a lack of trust and almost paternalistic mindset by employers towards FDWs, could contribute to their ill-treatment.

John shared that despite being a group of grown women, he often encounters domestic workers who are referred to as ‘girls’ and employers who don’t give them days off because they worry about domestic workers getting into ‘bad company’.

More often than not, these same employers allow their teenage children to go out far more freely. Jolovan Wham, past executive director of HOME, adds that this lack of trust and paternalistic mindset extends to other areas of a domestic workers’ life.

For instance, some employers may safekeep salaries of their domestic workers on the reasoning that domestic workers do not know how to manage their money. Other employers may keep their domestic worker’s passports out of a fear that they would abscond and the employer would lose their $5,000 security bond.

Bhing, a domestic worker, expressed her view that the need to ‘protect’ domestic workers is irrational and implored employers to treat their domestic workers like any normal working adult. They need rest and are able to ask for help if they need to.

“Having fun on their off-days will not affect their professionalism when they are working. Off-days can also be valuable time for them to sort out their personal problems, which can be extremely challenging when they are separated from their families,” she said.

She suggested that employers can begin to nurture trust with their domestic worker by engaging in more conversations to learn more about them. Instead of restricting their actions out of a fear of ‘bad behaviour’, they could caution their domestic workers about the potential dangers they may come across on their off-days and educate them on how to avoid these dangers.

• • •

Improving the welfare of our FDWs

Besides encouraging bystanders to act, what else can we do to improve the welfare of our FDWs and prevent ill-treatment, or even abuse?

Instead of accusing someone of being a bad employer or a bad FDW, Phoebe from MaidForMore believes that creating change in this area requires us to ask ourselves: why do we believe our domestic workers should not have access to certain conditions of work and living? If we are able to provide these conditions, why are we withholding them?

Phoebe suggests exploring the following:

• Living 24/7 with one’s employer can be extremely stressful and the physical isolation dangerously increases the likelihood of abuse. Could living outside of their place of work, such as in a dormitory like our migrant workers, be an option for domestic workers?

• Could access to mobile phones for our domestic workers be mandated?

• Could the interviews by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) for newly deployed domestic workers be scheduled within a month of their deployment, compared to the current three to six months after deployment?

• To alleviate tensions arising from language barriers, could English lessons be provided for our domestic workers and could employers provide for time off for their domestic workers to attend these courses?

John from TWC2 expressed his hope that the power to confine and isolate a domestic worker should be abolished. “It should be made relatively simple for a domestic worker to change employers, just like a Singaporean can,” he said.

Could more support be provided to empower domestic workers to speak up for themselves, as opposed to educating bystanders to act on their behalf. Might that make a much bigger difference as to how they are treated?

John also suggested using a portion of the foreign worker levies to subsidise care workers so that domestic workers are able to have a day of rest. He observed that some domestic workers are paid to give up their day off to provide care for their employer’s families as employers are unable to do so themselves.

“Instead of the default setting being ‘get the maid to do it’, could it be ‘get the government to take care of it’?”

• • •

In putting together this article, I learnt how the bystander effect could stem from the unequal relationship between employers and domestic workers, how social media can normalise a negative perception of FDWs and how a lack of trust and paternalistic mindset by employers towards their FDWs can contribute to the ill-treatment of and even abuse of our domestic workers.

Do you think there are other factors affecting the how we treat our domestic workers as a society? Do you agree with the recommendations put forth by those I interviewed?

Let us know by leaving a comment below! For more content like this, subscribe to our mailing list at agoodspace.org/blog/

See Tow Jo Ann

Jo Ann is a content marketing intern at A Good Space. She loves a good day at home with Netflix, or even better, mahjong.