Like many Singaporeans, I grew up quickly learning to accept the narrative that our nation had successfully achieved racial harmony.

Social Studies classes taught us that the 1964 racial riots were the chaotic consequence of what can happen when racial tensions go unchecked. This fear of history repeating itself has perhaps made racial issues a very sensitive topic and maybe led to our collective lack of proficiency in navigating any form of dialogue regarding race.

“We know we can no longer not talk about it. But how to talk about it is something we are grappling with.”

Mohamed Imran Mohamed Taib, founding board member of the Centre for Interfaith Understanding

Yet with the recent displays (and documentation) of overt racism in Singapore, and as the debate on race continues to play out online, it has become clear that these conversations need to be had.

The question then becomes:

How can we talk about race and racism constructively?

I started doing some research and found interesting examples both locally and overseas that give us a glimpse into how difficult conversations can be facilitated. In this article, I share three of them that I found, followed by my own thoughts on why these approaches were effective.

#1: Museum Exhibitions

Museums possess great potential to be a site of discussion, healing and community building. The demographic of museum-goers are becoming more socially and culturally diverse and they are also interacting with exhibitions as active participants, thereby placing higher demands on museums to create opportunities for meaningful audience participation and engagement.

As museums become key public spaces, they have to be more mindful about inclusivity by adopting a collaborative approach with the communities they serve.

The Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) offers a pertinent example of how transformative this approach can be. Earlier this year, the travelling exhibit about the life of Nelson Mandela made its United States debut, with the MPM as its first host.

During the exhibition’s press conference, president and CEO of MPM, Dr. Ellen Censky talked about how it would be “disingenuous for MPM to present this exhibit without meaningful partnership with the African American community”.

Thus, to address the sensitivity around having a single (largely white) organisation presenting an exhibit on such an iconic symbol of Black resistance, MPM sought the partnership of America’s Black Holocaust Museum (ABHM), another museum in Milwaukee dedicated to raising awareness about the African-American experience and promoting racial repair, reconciliation and healing.

Besides that, the MPM also consulted a diverse, 50-member advisory committee comprising community leaders, youth groups, academics and other institutions to provide diverse perspectives and ideas that helped shape the exhibition’s programme.

This led to the creation of events in parallel to the exhibition that highlighted how various ground-up initiatives were contributing to the changing social and racial justice landscapes of Milwaukee. This was arguably possible because of how many groups and communities were involved in planning this exhibition.

Thus, I think the most important takeaway from Milwaukee’s museums is that collaboration is productive. When we listen into the combined knowledge of museum staff, academics, youths, community groups and visitors, we can begin to surface biases, prejudices and assumptions that might have been invisible to us — all of which are so important to an effective facilitation of conversations about race.

#2: Middle Ground

In 2016, Janil Puthucheary, chairperson of OnePeople.sg, the national body promoting harmony, conducted a social experiment called a Privilege Walk to provide a visual representation of race-based privilege in Singapore.

While the experiment allowed the participants to reflect upon their racial privilege and the disparity between themselves and others in society, there has also been critique online about how privilege walks in general can be unproductive. This perspective says that although privilege walks may be a good way for people to examine privilege and create potential ways into difficult conversations, if there is no inherent call to action, privilege walks may lead to shame and further segregation.

The privilege walk in the video above seemed to have concluded with a dialogue session. However, since this portion of the experiment was overlaid with interview clips of individual participants, it is unclear whether they were presented with a clear call to action or what that call to action was.

Youtube channel Jubilee has a thought-provoking series (among others) called Middle Ground that, in my opinion, offers a more conducive alternative to privilege walks. It goes something like this:

Two groups of people with opposing beliefs about a topic (pro-life/pro-choice, voters/non-voters, pro-drugs/anti-drugs etc.) are invited to sit in a circle. They are presented with statements about the topic and must first indicate whether they agree or disagree with the statement. They then take turns explaining their answer, engaging in conversations that work towards deeper connection, empathy and understanding.

I personally really enjoyed the format of this series; specifically how the participants are made to offer a cursory stance (agree or disagree) before expounding upon their decision.

In this way, even as a viewer, I was able to experience having my assumptions and inherent biases challenged. There were many instances where I caught myself judging participants for their initial response, only to find myself agreeing with some of their points after listening to their justifications.

Although Jubilee has produced a few Middle Ground videos focusing on race, I wanted to highlight a particular episode between Israelis and Palestinians.

Because of the sensitive nature of the topic, I was fully expecting the participants to be yelling over each other and not wanting to truly engage in conversation with the other side (much like the current discourse on race that we sometimes see here in Singapore).

However, what I found was the exact opposite. Their conversation demonstrated an admirable example of effective nonviolent communication that, against all odds, revealed similarities and connection between even the most dissenting participants.

For me, the key to the effectiveness of that particular conversation was the language used by the participants; “I have these views but I understand where you are coming from”, “I respect that you feel that way”, “I’m sorry you went through that”, “I feel your grief”, “Thank you for sharing”.

Thus, although the episode did not touch on the topic of race, I think it is worth learning from their practice of having participants affirm each other’s emotions and experiences, which enabled them to have a civil discussion while still connecting authentically with each other, despite having completely different views.

#3: AI-Powered Research

Even if we incorporated diverse voices into the conversation, or learned to effectively use nonviolent communication, how do we then ensure that these conversations are generative in crafting tangible and effective solutions for a better future?

Enter OPPi, an AI-powered polling tool that can gather opinions from the public and sieve through ideas and perspectives to uncover: where are we similar and where are we different?

OPPi believes that locating these “glue lines and fault lines” that exist in our society is a crucial step in effectively addressing complex social issues.

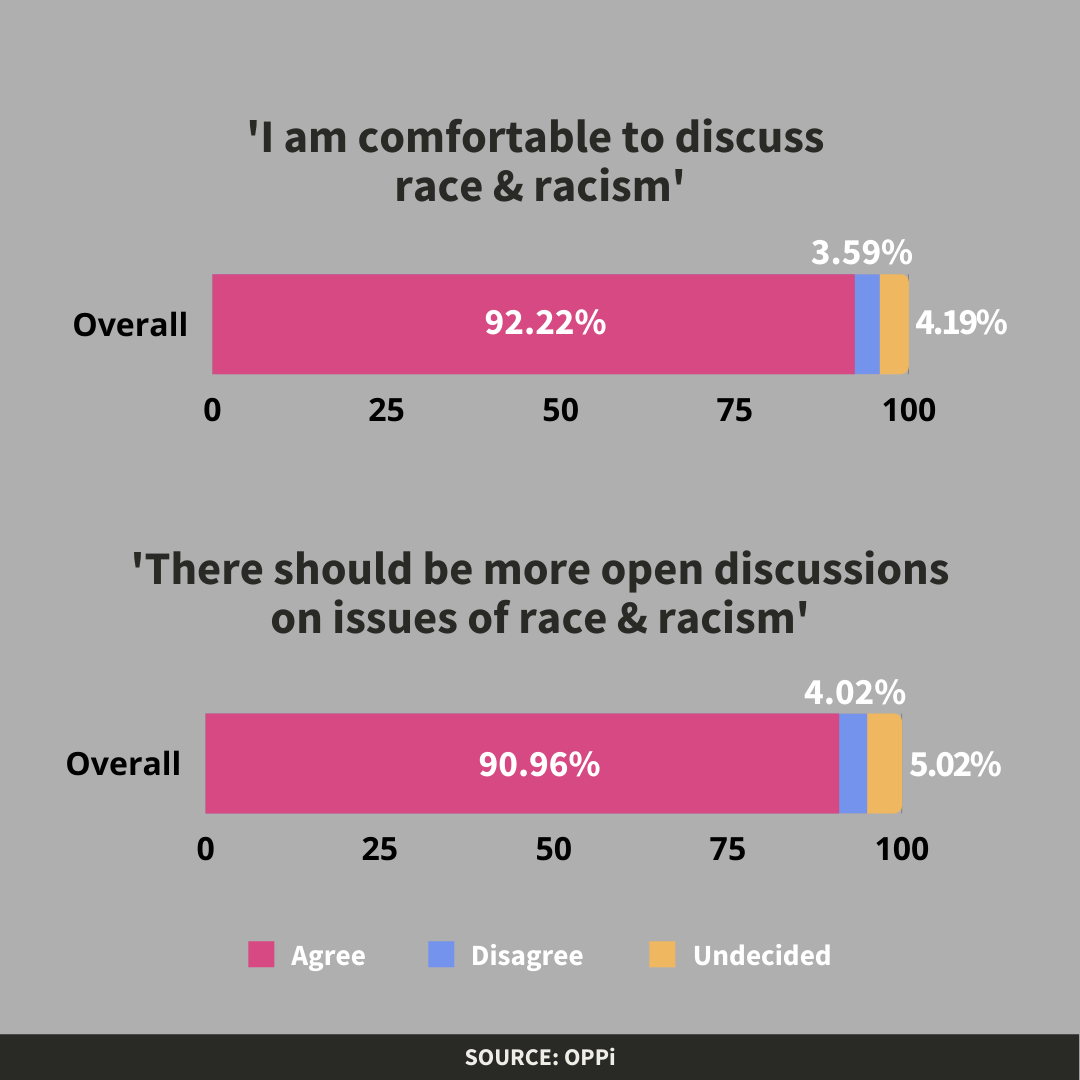

Last year, the OPPi team, including A Good Space member Santosh Kumar, conducted a poll to provide a pulse check on issues related to race and racism in Singapore that aptly demonstrates this process.

Among their 503 poll respondents, over 90% indicated that they were comfortable discussing race and racism, and agreed that we should have more open discussions on these issues. This overwhelmingly unanimous statistic directly challenges the view that Singaporeans are not ready to have these conversations.

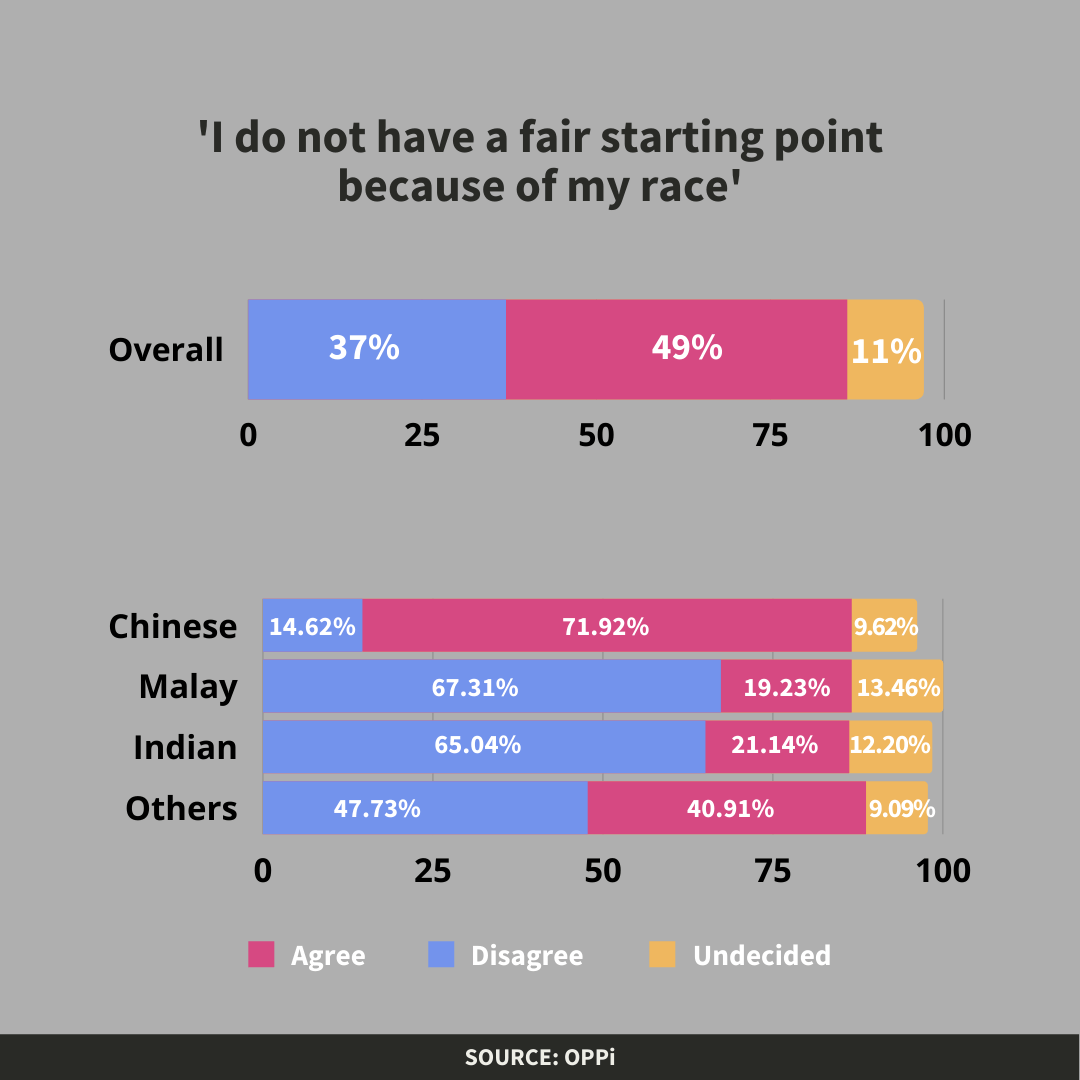

The poll also revealed significant differences between majority and minority races. For instance, when asked if they had a fair starting point because of their race, the overall response suggested that half of the participants disagreed with the statement.

However, when broken down based on the respondents’ race, the percentage of respondents that disagreed with the statement jumped from 49% overall to 71.92% among Chinese respondents. In contrast, that percentage dropped to around 20% among both Malay and Indian respondents.

What this set of data tells us is that the issue of fairness is where the division lies. The intensity of this particular fault line compared to the previously mentioned statements also suggests that this is a disparity that has yet to be addressed.

In many ways, OPPi’s ethos can be seen as a culmination of the first two examples in that it emphasises working with the participants to co-create solutions while simultaneously validating and facilitating the discussion of feelings and perspectives.

Conclusion

As I end off this article, a recurring theme is clear; at the heart of each of these examples is the desire for understanding and meaningful connections in spite of our differences.

The methods presented in this article will by no means solve systemic racism overnight. However, I think they can provide productive tools that allow us to enter any conversation about race with the intention of hearing, understanding and validating people’s concerns.

We invite you to join us at our upcoming event, Possibility Conversations (Race) where we hope to put these tools into practice.

Sign up here to be part of the conversation: http://bit.ly/pocoaug21

Come join our mailing list here if you would like to be updated when we write more articles like these!

Sin Melia

Melia is a Digital Marketing Trainee at A Good Space. She is a big fan of mother nature, tiger balm and food tiktok. You can probably find her somewhere over-analysing a TV show or K-drama.